Swallows, Amazons and Adventure

Jon Sparks muses on adventure in the life and work of Arthur Ransome

Last year I was invited to speak at the Arthur Ransome Society’s Literary Weekend in Harrogate. I delivered a modified version of a talk entitled 'Swallows, Amazons and Adventure', originally prepared for Kendal Mountain Festival. You can read the original text of the Kendal talk on my Ransome blog; what follows aims to catch the gist.

(I’ve also posted on my personal Substack about Ransome’s literary influence on me.)

After over 30 years, and 60 books, as an (award-winning) outdoor writer and photographer, Jon Sparks has recently switched his focus to fiction. Find out more from his website.

If you didn’t already, you can subscribe to OWPG’s Substack, for free, to receive new posts and support our work.

Adventure in Ransome's Life

Family holidays at Nibthwaite, at the foot of Coniston Water, engendered Ransome’s lifelong (1884—1967) love of the Lakes. Even as a young boy, he often roamed the countryside alone, and spent days in a rowing boat with his fishing-mad father. As a young man he returned frequently to Coniston, getting to know the Collingwood family, who lived near the head of the lake, and with whom he shared early experiences of sailing.

Partly to escape from a disastrous marriage, Ransome went to Russia in 1913, ostensibly to study fairytales'. He’d shown little previous interest in politics or news-journalism, but found himself an eyewitness to the Revolutions of 1917 and ensuing conflict.

In terms of 'adventure' it’s hard to beat his story of crossing the battlefront of the Civil War and approaching the 'Red' front-line calmly smoking a pipe and carrying nothing more threatening than a portable typewriter.

In 1917, in St Petersburg, he met and fell in love with Trotsky’s secretary, Evgenia Shelepina. In 1919 they moved to Estonia and later to Latvia, and explored the Gulf of Finland; Racundra’s First Cruise became a yachting classic. Once free to marry, they returned to England in 1924.

For some years Ransome was a regular foreign correspondent for the Manchester Guardian, visiting China and Egypt, but fretted that he was running out of time to focus on what he felt was his real calling: writing stories. In 1925 Arthur and Evgenia settled in the Lakes, at Low Ludderburn near the foot of Windermere, and he sailed here and on Coniston Water with friends and their children. Many places in the books can be directly linked to real-world locations on and around the two lakes, though the geography is extensively rearranged and names are changed. I’ve explored these connections in books and articles, as have others.

In 1929, he gave up being a foreign correspondent. He describes it as ‘a hinge year ... joining and dividing two different lives.’ It was the year in which he wrote Swallows and Amazons, published the following year. If his own life thereafter seems less adventurous, it wasn’t without its moments, but much that went into the books was distilled from the experiences of his first forty-five years.

Sailing

When it came to sailing, Ransome knew his stuff. By the time of Swallows and Amazons, he'd been sailing in the Lakes for years, and made those Baltic cruises. In later years he explored the waterways of East Anglia and crossed the Channel and North Sea.

In the books the young protagonists often sail entirely on their own. InSwallows and Amazons, John, aged 11 or 12, is skippering three younger siblings. It’s all made possible by a telegram from their absent father: Better drowned than duffers. If not duffers won't drown.

People more expert than me have approved Ransome’s writing about sailing. My one real taste of life under sail was on the other side of the world, joining Bridget Carter (my partner’s sister) and Rod Hall on a stage of their protracted circumnavigation1 from Cairns up the North Queensland coast and across the Gulf of Carpentaria. In a nice resonance, years later, in a house overlooking the Bay of Islands, they introduced me to another Ransome-inspired author, Jon Tucker.

Mountaineering

Ransome may have been an experienced sailor, but he was never a mountaineer. As a younger man, he was a great walker, in the lowlands and on the fells, but I’ve seen no evidence that he ever experienced rock-climbing or mountaineering. This, I think, is evident in the two main 'mountaineering' episodes in the books.

The first of these is the ascent of 'Kanchenjunga' (his spelling) recounted in Swallowdale. The peak is based on Coniston Old Man, so prominent from around Coniston Water.

Why Kanchenjunga rather than Everest? Exploits on Everest would be fresh in memory, including Mallory and Irvine’s disappearance in 1924. However, Kangchenjunga (the usual spelling) was probably more famous then than now. Unlike Everest, it’s readily visible from populous areas, notably around Darjeeling, and had also attracted several attempts. The late Doug Scott, an OWPG member, rated Kangchenjunga as the most challenging of the world’s high peaks (he wrote an excellent book about it).

Then again it might just be that—as John says—'Kanchenjunga’s a gorgeous name anyhow.’

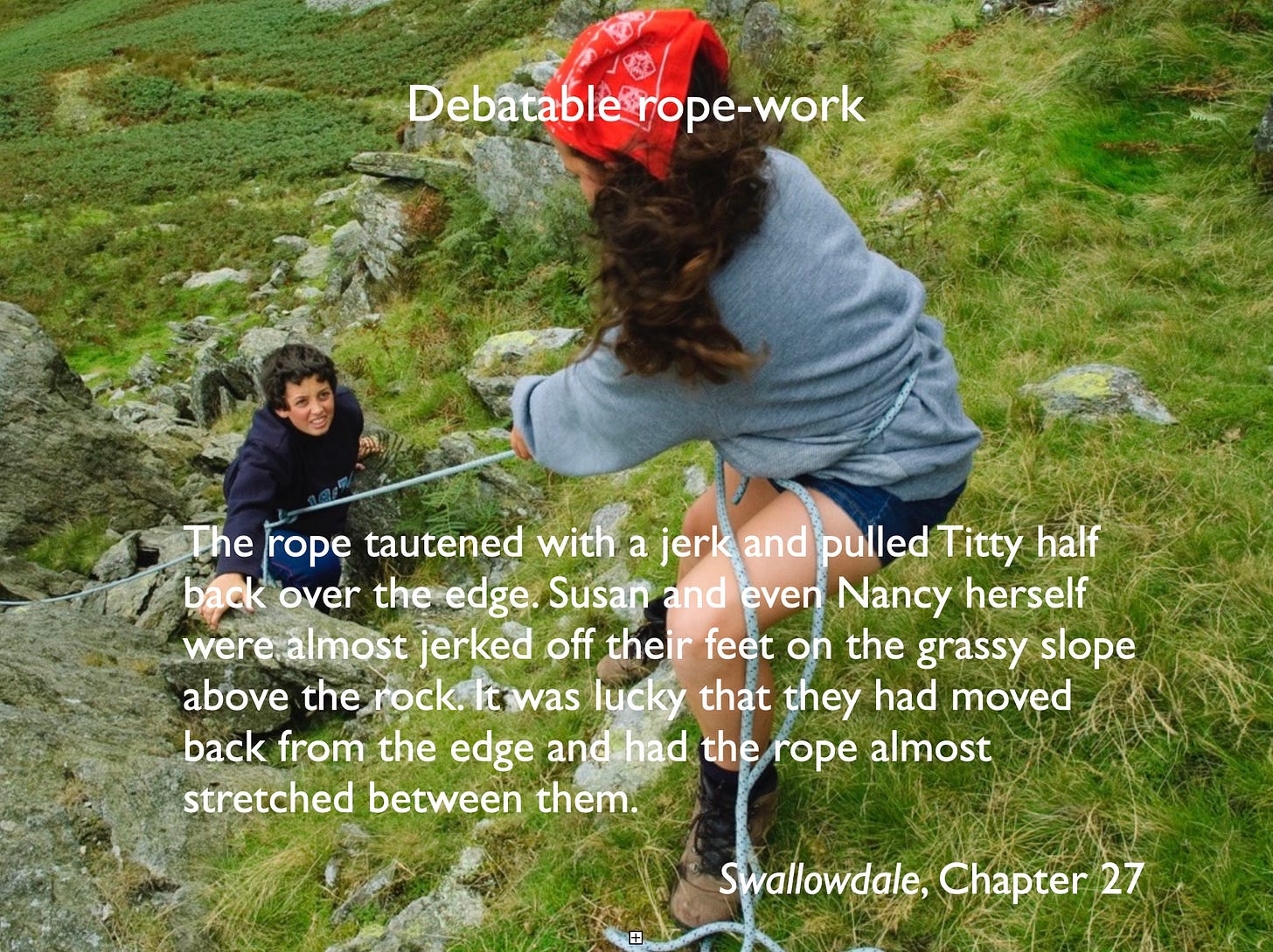

Be that as it may, the ascent of 'Kanchenjunga' in Swallowdale does not exactly follow recommended procedure. The eight children gaily proceed up the fellside, taking crags and outcrops in their stride, all tied on one rope but with no belays. It could all go horribly wrong, and very nearly does, when Roger slips.

Safety is even more dubious in Winter Holiday, when Dick rescues a cragfast sheep by traversing a narrow, icy ledge, secured only by the rope in the hands of Titty, Roger and Dorothea, with their feet 'well dug into the snow'. They lower the sheep hand over hand and are about to do the same for Dick when the others arrive.

Ransome seems to have skimped his research here. Lowering someone hand-over-hand is a lot harder than you might think, even with a rope that hasn’t been lying in the snow…

As the saying goes, 'do not try this at home'.

Bikes

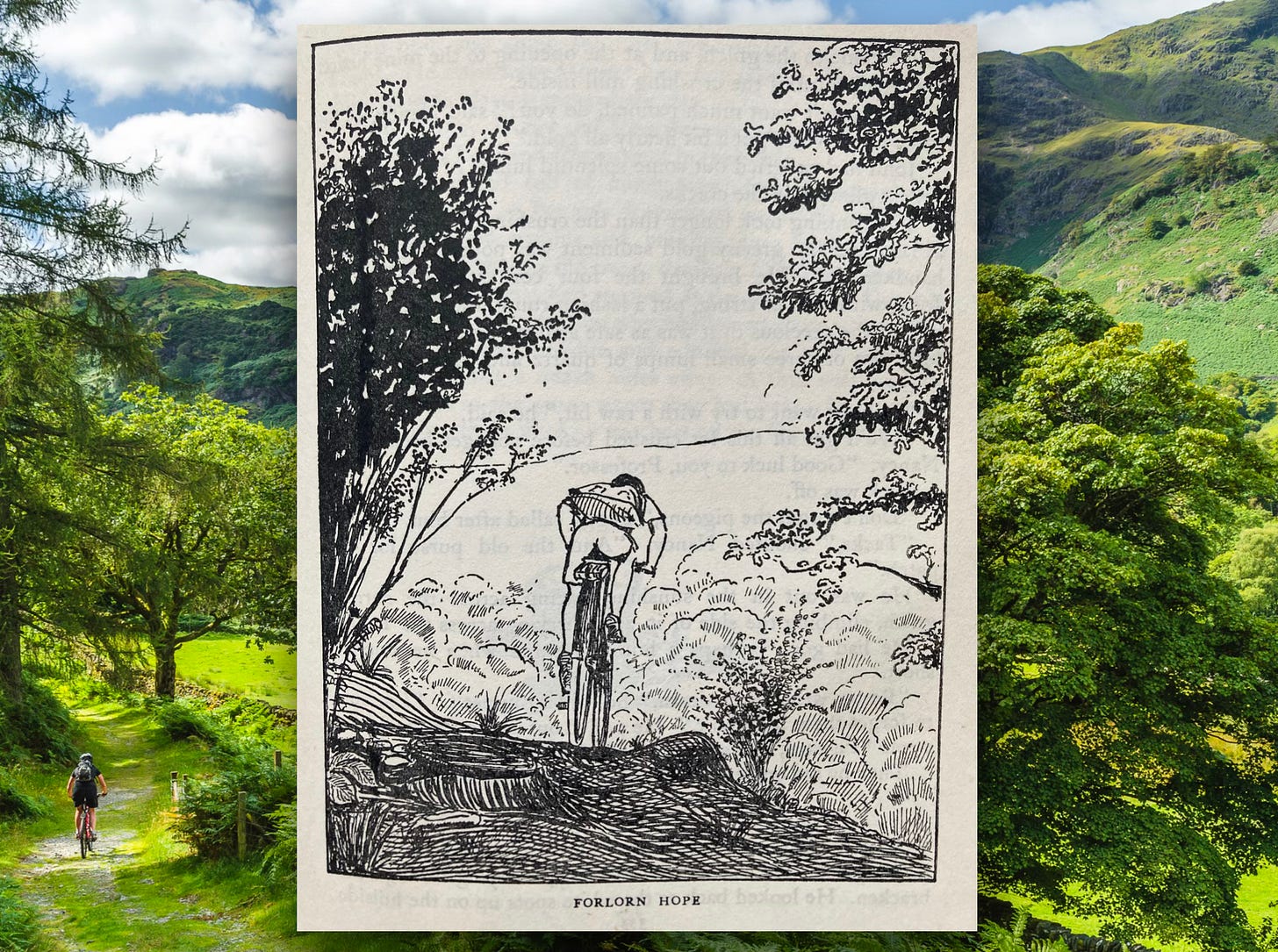

Bikes aren’t exactly central in the stories, but one episode in Pigeon Post intrigues me, as Dick, on Peggy's bike, hurries to Beckfoot to attempt the final assay to prove that what they've found is gold.

What was his ride actually like? It’s obviously rough, and the illustration (one of Ransome’s most dynamic) gives a fine impression of steepness. And Dick is on a 1930’s steel ‘girl’s bike two sizes too big for him’—and with a pigeon basket strapped to the handlebars! He’s entirely alone, and probably no older than 11.

Having ridden many Lakeland trails on modern mountain bikes, and more recently on a gravel bike, I have a strong impression that Dick’s ride was close to the ragged edge. (See my blog post Dick Callum – Pioneer Mountain Biker?)

Exploration

The children, especially the Swallows, often see themselves as explorers, particularly in the first four Lake District books and Secret Water, with its focus on filling in blanks on a map.

There's even a reference to exploration prefacing Chapter One of Swallows and Amazons, quoting Keats’s On First Looking into Chapman's Homer.

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star'd at the Pacific—and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

The theme of exploration is most central in Winter Holiday. This was published in 1933, when the exploits of Scott, Shackleton, and Amundsen were still fresh in collective memory, so it may seem odd that Ransome never mentions any of these names, only the great Norwegian, Fridtjof Nansen. This is homage to a personal hero.

Winter Holiday explicitly references Nansen’s career as an explorer, mentioning his two classic books, The First Crossing of Greenland (1890) and Farthest North (1897). Ransome met Nansen in Rīga in 1921, when Nansen was engaged in humanitarian work, for which he received the Nobel Peace Prize.

In Winter Holiday the eight young explorers commandeer Captain Flint’s houseboat, turning it into Nansen’s Fram, experiment with sailing sledges and ‘cross Greenland’. A misread signal upsets carefully-laid plans and, instead of an orderly daytime journey, it all culminates in an exciting nocturnal dash to the 'North Pole'.

The Great Outdoors

In all Ransome’s books the children spend most of their time out of doors.

Many of us think we played outdoors as kids much more than today’s youngsters do, and solid research supports us. American writer Richard Louv described 'Nature Deficit Disorder', linking it to issues such as childhood obesity. The Glover Report, commissioned by the UK Government, and published in 2019, also highlights the importance of access to nature for all. I think it’s fair to say the last Government did shamefully little toward implementing its recommendations; will Labour do better?

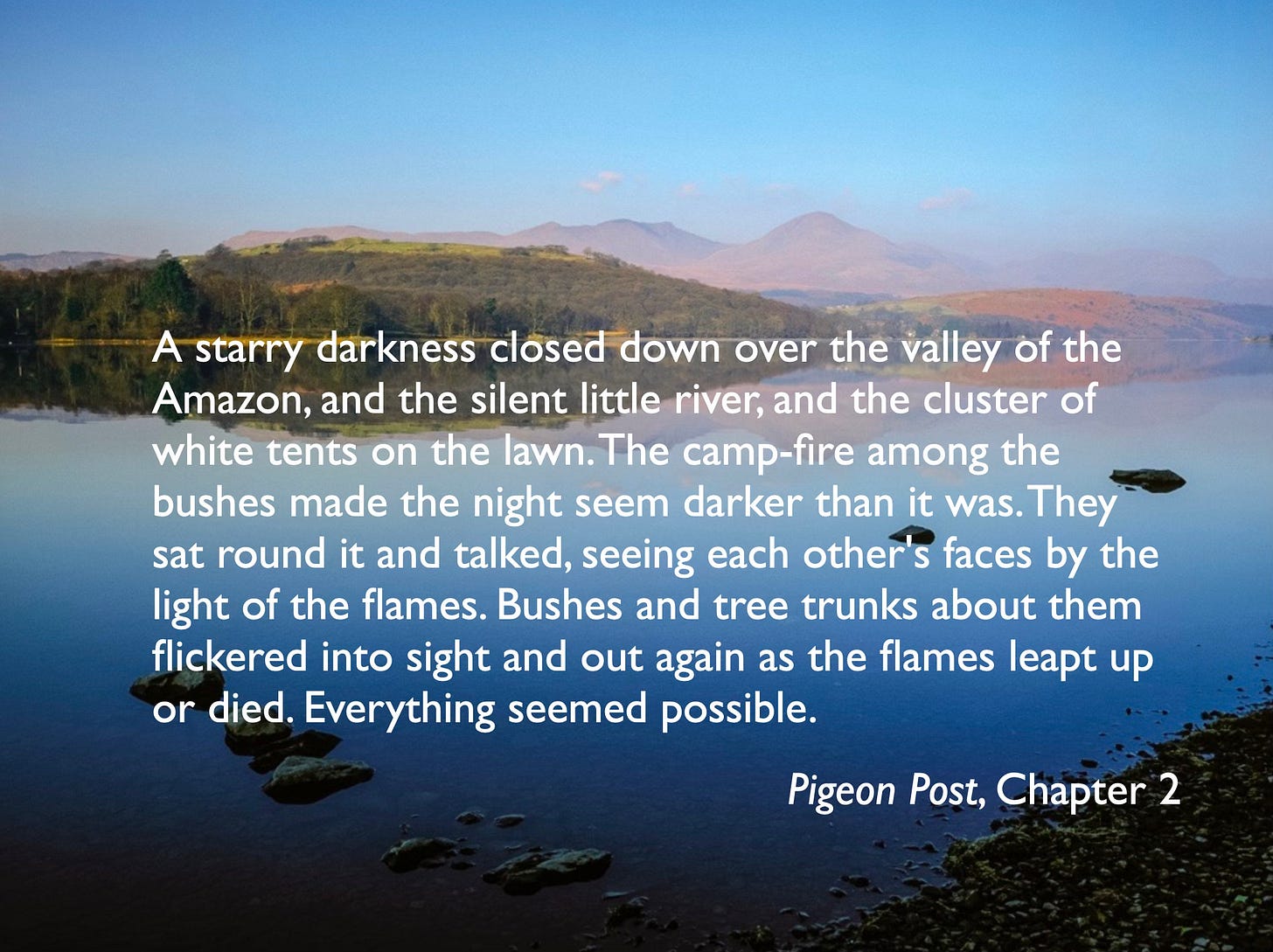

Swallows and Amazons, for example, is almost entirely an outdoor book, with a few pages of indoor preparations in Chapter 2, and only fleeting visits to the indoor world thereafter. Here, and in several other books, they camp, and it’s what we today would call ‘wild camping’, away from adults, cooking their own meals, quite independent. The children also sail, and roam the fells with little or no adult supervision. Often no adult even knows where they are. The parental attitude seems to be encapsulated in the famous 'duffers’ telegram in Swallows and Amazons.

In Swallows and Amazons, during the climactic 'war', Titty is left on Wild Cat Island alone. Her mother pays a visit, but then rows away and leaves her alone again. She’s nine. And meanwhile, the rest of them are sailing up and down the lake in the dark…

They repeatedly face genuine risks, and sometimes feel the consequences.

If hazard is common, genuinely life-threatening situations are rare, outwith the fantastical Peter Duck and Missee Lee. In my estimation, Dick's rescue of the cragfast sheep in Winter Holiday is where the margin of safety is stretched thinnest, though this may not be apparent to the average reader. The most sustained level of genuine risk is surely in We Didn't Mean To Go To Sea, which sees the four Swallows, the oldest still only thirteen, crossing the North Sea at night in an unfamiliar yacht.

Freedom for all

Themes like exploration and piracy are, or were, often associated with muscularity and masculinity. Some of the children’s own reference points, like Treasure Island or Farthest North, are almost exclusively male. However, Ransome’s stories feature several strong and significant female characters. In the Lake District books, there are always more girls than boys; girls are a minority only in Coot Club and The Big Six2.

And they’re not there just to make up the numbers. The story is often told from the point of view of one while all, in various ways, display competence beyond traditional female roles. Most obviously, there’s Nancy Blackett, so often the leader, but (perhaps surprisingly) hardly ever the point-of-view character, yielding this to Titty or Dorothea.

Starting with Winter Holiday, the empathetic and observant Dorothea often gives us insight into the characters of the others. I suppose Dorothea resonated with me as I too was a voracious reader and an aspiring writer; I’d like to think she gave me a bit of a nudge in that direction.

It’s now 94 years since the publication of Swallows and Amazons. Can Ransome's books still resonate with today's youngsters, particularly those from more marginalised communities? To end on a hopeful note, I'll just mention that the person who chose to talk about Ransome for the R4 series Great Lives a few years ago was a gay black man, Labi Siffre. Dare we hope that there are still young people, of all backgrounds, who are finding inspiration in the works of Arthur Ransome?

If you’re curious to know more about their story, check out this post on my personal Substack, which also links to my original magazine feature about it.

Three girls to five boys in Coot Club, but in The Big Six, Dorothea is the only girl. She does, however, mastermind the investigation which lies at the heart of the story.

Thank you, that was a real trip down memory lane! I adored those books as a child and read and reread them. In life I have always found it a personal goal to explore and make sure that any 'north west passage' is found and explored before moving on. I must read them again.

Someone on Substack mentioned Winter Holiday recently so I decided to reread it. You’re so right about Dick and the crag fast sheep!

I spent hours as a child drawing maps inspired by Swallows and Amazons.